A CONCEPTUAL MODEL PROPOSAL ON PUSH AND PULL FACTORS IN MIGRATION TO EUROPEAN UNION COUNTRIES

Arş.Gör.Özge Çetiner tarafındanThis study was written in Turkish, and its translation was carried out by Young Diplomats. (Original study available at: https://doi.org/10.30794/pausbed.1413160 )

Abstract

Human capital is accepted as an indicator of individuals' education, experience, knowledge and skills. Having a high level of human capital is one of the factors that facilitates the process of adaptation for immigrants to their new country of residence. On the other hand, the level of human development attracts immigrants to these regions with factors such as better living conditions, human rights and employment opportunities. Therefore, countries with strong human capital and human development elements are attractive for people who want to migrate due to features such as strong labor markets, quality of life, educational opportunities and economic development. The aim of this study is to examine the impact of human capital on migration in European Union (EU) countries through the mediating roles of human development and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. In this context, a model proposal was presented and path analysis was carried out with SEM with the data of EU countries between 2000 and 2020. Analysis findings show that human capital has a significant and positive effect on migration. On the other hand, it was concluded that human development and GDP per capita mediate the relationship between human capital and migration.

Keywords: Human capital, Human development, Migration, GDP, Path analysis

- INTRODUCTION

Migration is defined as the process of moving, relocating and covering distance from one place to another. Migration is an important phenomenon due to its impact on the economy, society, politics and culture. Social mobility is expressed through migration, which is a process that maintains its validity and uniqueness in terms of its causes and consequences (İslamoğlu et al., 2014: 68). Many developments in the international system, such as the Arab Spring process that started in the Middle East and North Africa region in 2011, the transformation of these turmoil into violent conflicts, especially in Syria, the start of the Russia-Ukraine War in 2022, and the Taliban's regaining power in the region after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, have caused consequences that trigger migration by affecting mainly human security. With the change in global economic balances after the pandemic and the addition of climate change to these military security problems, migration movements have intensified and started to come to the fore in recent years. At this point, for example, in 2020, approximately 1.9 million people migrated from non-EU countries to the EU and approximately 956,000 people migrated from the EU to a country outside the EU. In 2021, there was an increase in these numbers, with 2.3 million people migrating from non-EU countries to the EU and 1.1 million people migrating from the EU to a country outside the EU (Eurostat, 2023).

One of the theories developed to better understand these intense migration flows is the theory of push and pull factors. The main assumption of the theory is that migration is determined by push and pull factors. The theory of push and pull factors examines the conditions that cause individuals to exit the country of origin and influence their choice of a specific target country. These factors are the forces that attract people to move to a new geography, but they also cover economic, social, political or environmental issues (Khalid and Urbański, 2021: 247). Therefore, these can be evaluated from many perspectives such as welfare level, social opportunities, access to basic needs such as education and health, freedom of expression, human rights, and the rule of law. At this point, the human development index and human capital can also be classified among the attractive factors. In other words, high welfare level, provision of adequate educational opportunities, access to health facilities and the quality of human capital are among the conditions that affect the choice of target country of migrants. Marger (2001), who supports this approach, emphasized that social opportunities and human capital are key factors not only in the selection of the destination country but also in the adaptation process of immigrants to this country.

There are various studies in the literature examining the links between human capital, human development, economic welfare and migration. Within the scope of the literature investigating the relationship between migration and economic welfare, Icduygu et al. (2001) used the data of the 1995 Turkey District Socio-Economic Development Index and the 1990 Census to reveal that migration flows are directed to regions with very low or very high economic development, as well as to regions with very low or very high economic development. Popogbe and Adeosun (2022), who examined the relationship between migration and economic welfare through the example of Nigeria, found that population growth rate and high unemployment rates were among the driving factors of migration from Nigeria to developed countries between 1990 and 2019, and that the increase in infant mortality rates reduced this migration. In addition, Roy and Debnath (2011) stated that migration is linked to income level, unemployment rate and cost of living, similar to the studies in the literature, but concluded that the crime rate is an unimportant issue among the criteria that determine migration, and therefore it focuses on basic needs instead of the living conditions of migrants. In his study, Mendola (2012) conducted a comprehensive review of the socio-economic literature to examine the relationship between local and international labor migration and economic development, focusing especially on external migration from poor rural areas. Arı and Yıldız (2018) discussed the common and different migration determinants in OECD countries with the cluster analysis method within the scope of 2015 data and determined that Turkey, USA, Poland, Hungary, Chile, Mexico, Slovakia and Czech Republic are in the same category.

Among the literature that deals with the effect of migration on economic development in the opposite direction, as well as the effect of economic welfare on migration, Kanbir (2022) reminded that human capital is one of the most important elements of economic development and pointed out that the country that attracts human capital earns high-quality labor at low costs. Similarly, Göv and Dürrü (2017) used the data of 7 OECD member countries for the years 2000-2016 to examine the relationship between economic growth and migration and revealed that human capital migration had a positive impact on economic growth. On the connection between human capital and migration, Ritsilä and Ovaskainen (2001) found that highly educated people are more likely to move than the rest of the population, and that the regional characteristics of the region of origin and destination influence this decision. In addition, Checchi et al. (2007) emphasized in their study that human capital accumulation is among the main determinants of economic growth.

In a globalized world where the factors of production are becoming more and more mobile, human capital and capital inflows also affect migration movements in various ways. At this point, Sain (2023) discussed the economic consequences of human capital loss through the example of Turkey and revealed that the cost of this to Turkey is approximately 2 billion 115 million, based on the data of the Turkish Statistical Institute that 45 thousand qualified workforce migrate annually.

Among the studies on the link between human development and migration, Bakewell et al. (2009) conducted a study on the countries of the global South and stated that migration in developing regions contributes to human development in terms of income, human capital and broader processes of social and political change. Kandemir (2012), in his research on the role of factors determining human development (income, health and education) in migration flows, examined the human development indices of the countries with migration flows in 2011 and revealed that income-education-health factors were effective in migration flows in order of priority. The author pointed out that human development or increasing global welfare will be important factors in managing and stopping migration. Caponi (2010), who narrowed down this finding and examined the migration link between America and Mexico through the education factor, found that those with the highest and lowest education tended to migrate more than those with secondary education. Kaewnern et al. (2023) emphasized in their study that economic growth provides the necessary resources to support advances in human development on the one hand, and on the other hand, advances in human development (good health, income, education, etc.) support economic growth by increasing labor productivity. According to the authors, economic growth and human development naturally have a bidirectional link.

Making use of the studies in the literature, this study evaluates migration rates in EU member states through attractive factors. In this context, the aim of the study is to examine the relationship between human capital and migration and the role of human development and per capita income between this relationship. In this direction, a model proposal was presented and path analysis was made with YEM. This study deals with the complex relationships between human capital, migration, human development and economic development from a holistic perspective, making use of the fields of international relations and global development, which provide a strong scientific basis for the migration literature.

This study, which evaluates human development and human capital as attractive factors and evaluates their impact on migration through the data of EU member states between 2000-2020 through YEM and road analysis, consists of two parts. The first part of the study; It offers a review of the literature on migration, human capital and human development. In this context, push and pull factors migration theory is explained, human development index and the connection of human capital with pull factors are evaluated. The second part is about the introduction of the method of the study. In this section, firstly, the structural equation model is introduced and then explained together with the findings of the analysis carried out within the scope of the study.

- THE ROLE OF HUMAN CAPİTAL AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT İN THE PUSH-PULL FACTORS THEORY

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the phenomenon of migration, which means crossing an international border (external migration) or moving within a state (internal migration), is an issue that basically deals with the individual. Different approaches developed to understand this phenomenon, which includes various fields such as geography, economics, political science, international security, history and law, have brought about the theorization of the subject (Massey et al., 2014: 11). At this point, the push-pull factors theory is one of the theories that try to understand and explain international migration.

The Push-Pull Factors theory, which was discussed by Evertt S. Lee in his study titled "A Theory of Migration" in 1966, is explanatory in terms of understanding forced/voluntary migration (Yazan, 2014: 14). This theory examines the driving factors underlying the migration of people from the country of origin (source) to the destination country and the attractive factors that encourage these people to migrate within the scope of economic, environmental, social and political categories. Lee, on the other hand, pointed out in his study that there are negative (-), neutral (0) and positive (+) factors that direct individuals to migrate from the source country to the destination country and that these factors may differ between individuals or groups with the potential to migrate (Lee, 1966: 50). For example, the increase in gasoline prices is a negative (pushing) factor for a middle-income family or individual who owns a car, while it has a neutral meaning for low-income people who do not own a car.

Push factors affecting migration include conditions that force individuals to leave their habitats. This area, which encompasses numerous examples such as low living standards, economic problems, conflict, drought, famine, various forms of discrimination (ethnic, religious, etc.), and political oppression, can generally be classified as economic, social, and political factors (Urbański, 2022: 3). Krishnakumar and Indumathi (2014: 9) point out that the main area affecting migration is economic factors. In developing countries, low income, employment problems and the low living standards caused by them are considered as the main factors pushing immigrants towards developed regions with more job opportunities (Hatch, 2016: 1). On the contrary, high living standards in developed countries and the opportunities to increase the income of individuals are opportunities that lead individuals to migrate (Llull, 2017: 1-2). In addition to economic factors, social factors such as lack of established health care systems, lack of educational opportunities, and political factors such as unfair legal systems, war, terrorism and mismanagement, and individuals having better living conditions in other countries (Doerschler, 2006: 1101) also trigger migration. In addition, Oltman and Renshon (2017) have pointed out in recent years that ecological factors are the main driving factors behind migration.

The attractive factors of migration are generally better conditions in the target country. At this point, more advanced employment and housing opportunities, higher income, higher living standards, religious tolerance, better education and health opportunities, better provision of individual security, freedom and tolerance are factors that attract individuals to migrate towards the target country. The human development index draws attention to the fact that the welfare of countries does not depend only on the income of the country, on the contrary, the development of the country depends on human development and human development has a comprehensive structure that includes education and health factors. Since 1990, this index has been an alternative measure for the country's progress instead of GDP (Kaewnern et al., 2023: 2). The Human Development Reports, which are published regularly every year, emphasize that human development requires people to expand and enrich their options to ensure that they can live long and healthy lives, access resources for a "decent standard of living" and have cultural development tools (Lind, 2019: 409). In other words, economic (welfare standard) and non-economic (health and education standard) indicators are included together in the calculation of the human development index (Demir, 2006: 4). The welfare standard is based on the per capita income, the education standard is based on the literacy rate among adults and the average education period, and the health standard is based on the average life expectancy of individuals (Zanbak and Özgür, 2019: 177-178).

Another attractive factor discussed in this study is human capital. On the concept of human capital, Adam Smith stated that the qualifications of individuals also contribute to society and are effective in the development of the country by using the connection between the qualifications of individuals and human capital (Awan, 2012: 2199). This concept, which has developed from AdamSmith to the present day, has been expanded and theorized. In this context, human capital is considered as a set of values in the form of knowledge, skills and experience that are effective in the efficient use of production factors (Manga et al., 2015: 46). In other words, this concept is the education and experiences of the workforce that make a significant contribution to economic growth (Manga et al., 2015: 47). These values constitute a factor that contributes to the development of the country's economy by paving the way for technological development and using them in the economy.

The EU is one of the institutions that focuses on the human dimension of development and therefore on the economy, education and health. At this point, for example, economic criteria are among the Copenhagen criteria, which include the characteristics sought for the admission of candidate countries to EU membership, and the EU expects candidate countries to have a functioning market economy. Similarly, Nartgün, Kösterelioğlu and Sipahioğlu (2013: 82) stated that the economy and education levels in the EU are high and pointed out that the advanced education-economy levels in the EU can be interpreted as experts in production. In addition, within the scope of 2021 data, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland and Germany are the countries with the highest human development index in the EU (UNDP, 2021). Çoban and Yayar (2018: 649) stated that the democratization levels of EU countries and human development indices are directly proportional and that increasing democratization has a positive impact on the human development index.

These definitions also reveal the connection between human capital and human development index. At this point, for example, education, which is important in the formation of human capital, is a criterion that is effective in the evaluation of countries as a human development index. Similarly, the health standard in the human development index is also important for human capital. It will be linked to economic growth as the healthy individual will participate more and better in the production process and education process (Manga et al., 2015: 48). Therefore, these criteria used in the study are complementary to each other and allow a detailed examination to be carried out through the EU.

- METHOD AND ANALYSIS

- Structural Equation Modeling

According to the model proposed within the scope of this study, path analysis was performed with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to measure the direct and indirect impact. YEM is a concept and theory development technique that is increasing from social sciences to management discipline. In this technique, it is essential to evaluate the complex consisting of multiple hidden structures in terms of relationship measurement and structural theory (Mia et al., 2019: 56). In SEM, relationships between variables are defined by a series of equations that define the assumed relationship structures (Wirayuda et al., 2022: 3). SEM modeling includes measurement errors of both internal and external variables, multiple indicators, mutual causality, dependence and simultaneity. A variable in SEM can be both internal and external at the same time. In other words, a variable in the model can be both dependent and independent by being affected by another variable while affecting another variable at the same time (Elverdi & Atik, 2021: 189). Path analysis, on the other hand, is known as a type of multiple regression statistical analysis method used to model the relationships between multiple dependent variables and multiple independent variable layers (Chen et al., 2022: 5). The complex relationships between the variables in the model are visualized in the path diagram and help to facilitate the understanding of the model (Schumacker and Lomax, 2004: 4).

-

- Defining the Model's Dataset and Variables

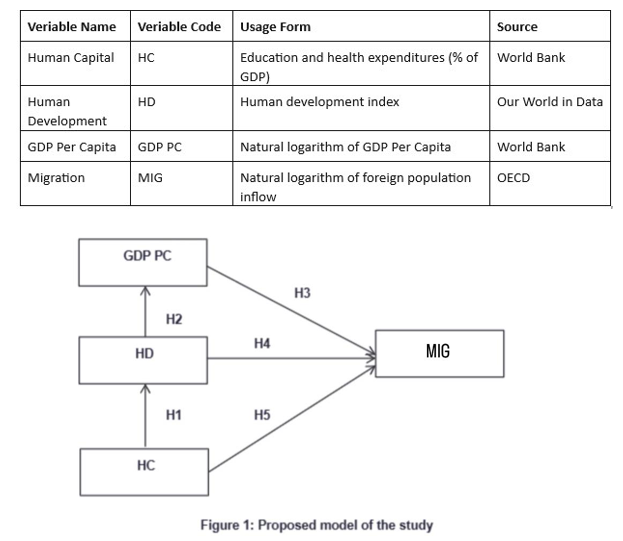

SPSS AMOS 29 package program was used for the analyzes performed within the scope of the study. AMOS is a highly popular software with a unique graphical interface for solving structural equation modeling problems. This software is widely used by researchers to perform comprehensive analyses by integrating various multivariate analysis methods such as regression, factor analysis, correlation and analysis of variance (Thakkar, 2020: 35). First of all, the variables and hypotheses in the proposed model were defined within the scope of the study. The dataset and hypotheses of the proposed model are as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 1: Dataset of the model

In the proposed model of the study, it is seen that the relationships of the variables with each other are handled in an integrated manner. In previous studies, these relationships have often been studied using separate models and datasets. However, in this study, all these relationships are evaluated under a single model and from an integrated perspective. This approach is expected to contribute to the literature and future researchers.

H1. Human capital has a positive effect on the human development index.

All investments in human resources such as education and health are considered human capital investments. It is important for sustainable development that people are educated and healthy, live in a free and fair society and use their skills in the labor market. Since factors such as health, education and living conditions are taken into account when calculating the human development index, this index is expected to increase with the increase in education level, improved living conditions and improved health services.

H2. The human development index has a positive effect on per capita income.

Although the human development index is a measure of human development in a country, indicators such as life expectancy, education and income are taken into account when calculating this index. Since this index indicates better human development, this development leads to a more productive and efficient workforce, higher levels of innovation and greater economic developments. As a result, higher levels of human development are associated with better economic opportunities, such as higher wages and better job prospects, which can attract immigrants seeking better living conditions and financial stability.

H3. Per capita income has a positive effect on migration.

Increasing earnings and per capita income reveal the potential to increase living standards, and this situation is among the important determinants of the value of a region and can affect migration decisions. Because the economic attractiveness of an area potentially encourages more people to move there. As per capita income increases, individuals can access higher education and health services, and higher levels of education and health services can help individuals find jobs and better prepare for their careers. These opportunities, which are attractive to people in other countries, affect individuals' migration decisions.

H4. The human development index has a positive effect on migration.

Better living conditions, healthcare, and educational opportunities are often associated with higher human development scores. This can increase the attractiveness of a country or region to people living in other places. Therefore, high levels of human development lead to an increase in migration to certain regions.

H5. Human capital has a positive effect on migration.

The development of education, health and human resources includes investments in human capital, which increases the level of education and qualifications in the labor market in the country. A country with higher human capital attracts more foreign immigrants and on the other hand, it encourages the exchange of knowledge and skills by providing skilled labor to employers. Therefore, these factors that increase the productivity of individuals or groups, such as education, health, work experience and other skills, are important for migrants to participate in the job market in the destination countries.

-

- Analysis and Findings

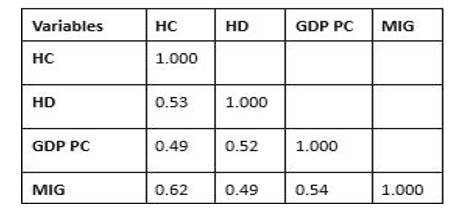

In this section, the necessary analyzes and findings for the proposed model within the scope of the study are included. In this context, correlation analysis was first performed. Correlation is a term used to indicate relationships between two or more quantitative variables (Gogtay and Thatte, 2017: 78). The correlation values between the variables are as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Correlation Values

When the correlation values in Table 2 are examined, it is seen that human capital has a positive correlation with all other variables. Human capital is 0.53 with human development and 0.53 with per capita income, respectively. It has correlation values of 0.49 and 0.62 units with migration. It is seen that the highest correlation value is between human capital and migration.

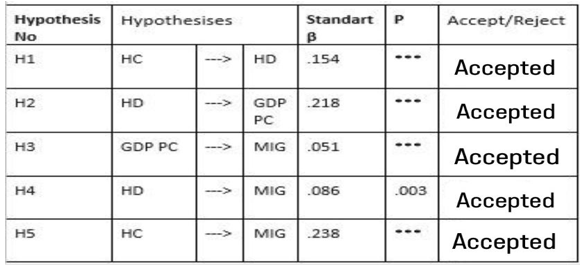

In YEM, hypotheses that are not supported by data are removed from the model and the model is reformulated. This conclusion contributes to making the model as precise and useful as possible. The SEM hypothesis test results of the model proposed within the scope of the study after the correlation analysis are as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Hypothesis Testing Results Of The Model

When Table 3 is examined, it is seen that all hypotheses in the model proposed within the scope of the study are accepted. Therefore, the analyzes will continue without any change in the model.

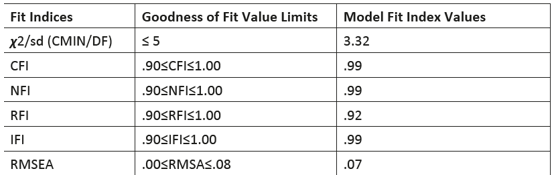

Other important values to look at in the SEM are the so-called goodness-of-fit indices. In SEM applications, the fit index values obtained as a result of the analysis are generally used to determine whether the model under study is supported by the collected data. It is accepted, rejected or corrected and changed based on the evaluation of the calculated goodness-of-fit indices (Yılmaz and Varol, 2015: 30). Although the researchers agree that χ2/sd should be given among the goodness-of-fit indices in SEM studies, they have made different suggestions about which of the other compliance indices should be reported (İlhan and Çetin, 2014: 31). When the literature was examined, it was observed that the other most frequently used goodness-of-fit indices in SEM studies were CFI, NFI, RFI, IFI and RMSEA (Byrne, 2010; Kennyet al., 2015; Savalei, 2018; Gürbüz, 2019). The goodness-of-fit value limits and the fit-index values of the proposed model are as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Model Goodness-of-Fit Indices

When Table 4 is examined, it is seen that the fit index values are within the acceptable goodness-of-fit limit ranges. This can be interpreted as the model being supported by the data used within the scope of the analysis. After the goodness-of-fit values, the path analysis findings of the model, in which the total, direct and indirect effects are shown, are as shown in Table 5.

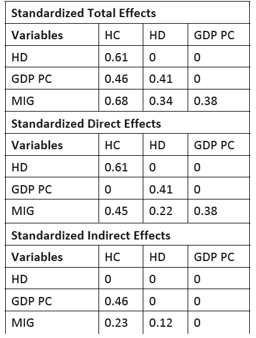

Table 5: Road Analysis Results

YEM examines the connections between variables from three perspectives. Direct effect occurs when there is no intermediary and one variable directly affects another variable. The situation in which one variable affects another through one agent is expressed as an indirect effect. The total effect level is calculated by adding these two effects. When the findings of the path analysis in Table 5 are examined, it is determined that human capital has a total effect of 0.61 units on human development, 0.46 units on GDP per capita and 0.68 units on migration. When the direct effects are examined, it is observed that human capital has an effect of 0.61 units on human development and 0.45 units on migration. When indirect effects are examined, it is determined that human capital has an effect of 0.46 units on GDP per capita and 0.23 units on migration. When the findings of the analysis are evaluated in general, it is seen that human development and GDP per capita mediate the relationship between human capital and migration. Of the total effect of human capital on migration of 0.68 units, 0.23 units is realized by intermediary effects. The study examines the positive effect of human capital on economic growth (Koç, 2013; Keskin, 2011; Yaylalı and Lebe, 2011; Yılmaz and Danışoğlu, 2017) confirms that it also applies to EU member states, but has shown that this also has an impact on migration.

- CONCLUSION

Migration is defined as the process of moving and relocating from one place to another, and it stands out as an important phenomenon that has deep effects on the economy, society, politics and culture. Especially in recent years, the change in global economic balances, the pressures created by climate change and security problems in various regions have led to the intensification of migration movements and an increase in studies in this field. The aim of this study is to examine the effects of basic economic and social variables such as human capital, GDP per capita and human development on migration from a holistic perspective. The study aims to better understand the causes and consequences of migration and aims to increase the effectiveness of strategies to be created in this field. In this context, the study examines human capital and human development index data as attractive factors for EU member states and examines the connection of these data with migration by comparing them over EU member states. In this direction, a model proposal was presented using the data of EU countries for the period 2000-2020 and the impact of human capital on migration was evaluated with the mediating roles of human development and GDP per capita. In the model proposal in which five hypotheses were tested, the analyzes were carried out with SEM pathway analysis and AMOS 29 package program.

After the analysis, the model proposal established within the scope of the study and five hypotheses were accepted. When the results of the road analysis were summarized, it was determined that human capital affected migration by 0.68 units, GDP per capita by 0.46 units, and human development by 0.61 units. In light of these findings, when evaluating the ranking of factors influencing migration (namely human capital, human development, and GDP per capita, respectively), it becomes evident that the primary factor driving migration to the EU is investment in individuals. In other words, the fact that human capital, which is a whole of the knowledge, skills and experience values required for the efficient use of production factors, and human development, which includes welfare-education-health standards, are in the first two places, shows that immigrants do not only focus on economic gains. When the indirect effects are examined, it is determined that human capital affects migration by 0.23 units and GDP per capita by 0.46 units. In other words, GDP per capita and human development mediate the relationship between human capital and migration. These findings show that countries with high levels of investment in human capital and economic prosperity tend to attract more immigrants than other countries. In particular, these results suggest that education, health and labour market policies should be designed to strengthen human capital while also promoting economic growth. Such holistic approaches will enable more effective management of migration and human development and contribute to the achievement of sustainable development goals in these areas. In addition, implementing policies that strengthen the link between economic growth and human development will be critical for both short-term results and long-term sustainability

In the analysis of the study, developed countries were evaluated on the basis of attractive factors. New studies may focus on the driving factors that lead individuals in developing countries to migrate. In addition, new studies can develop different models using different variables and contribute to the development of the literature that tries to understand and explain migration by comparing and interpreting variables.

Bibliography

Arı, E. ve Yıldız, A. (2018). “OECD ülkelerinin göç istatistikleri bakımından bulanık kümeleme analizi ile incelenmesi”, Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 33, 17-28.

Awan, A. G. (2012). “Diverging trends of human capital in BRIC countries”, International Journal of Asian Social Science, 2(12), 2195-2219.

Aylin, K. (2013). “Beşeri sermaye ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi: Yatay kesit analizi ile AB ülkeleri üzerine bir değerlendirme”, Maliye Dergisi, 165, 241-285.

Bakewell, O., de Haas, H., Castles, S., Vezzoli, S. ve Jónsson, G. (2009). South-South migration and human development: reflection on African experiences. International Migration Institute Working Papers.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modelling with Amos. Routledge, New York.

Caponi, V. (2010). “Heterogeneous Human Capital and Migration: Who migrates from Mexico to the US?”, Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, 207-234.

Checchi, D., De Simone, G. Ve Faini, R. (2007). “Skilled migration, FDI and human capital investment”, Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano Development Studies Working Paper, No. 235.

Chen, S., Wang, T., Bao, Z. ve Lou, V. (2022).” A path analysis of the effect of neighborhood built environment on public health of older adults: a Hong Kong study”, Frontiers in public health, 10, 861836.

Çoban, M. N. ve Yayar, R. (2018). “Demokrasinin Göstergelerinin İnsani Gelişmişlik Üzerine Etkisi: AB Ülkeleri Üzerine Bir Panel Veri Analizi”, International Journal of Academic Value Studies, 4(20), 642-651.

Demir, S. (2006). “Birleşmiş Milletler kalkınma programı insani gelişme endeksi ve Türkiye açısından değerlendirme”, Devlet Planlama Teşkilatı: 1-22.

Doerschler, P. (2006). “Push-pull factors and immigrant political integration in Germany”, Social Science Quarterly, 87, 1100–16.

Dünya Bankası. (2023). World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/, (erişim tarihi: 09.09.2023).

Elverdi, S. ve Atik, H. (2021). “İnovasyon ve ekonomik büyüme arasındaki ilişkinin analizi: Bir yapısal eşitlik modellemesi”, Pearson Journal, 6(10), 183-205.

Eurostat. (2023). Migration and migrant population statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics#:~:text=%3A%20Eurostat%20(migr_imm2ctz)-,Migrant%20population%3A%2023.8%20million%20non%2DEU%20citizens%20living%20in%20the,5.3%20%25%20of%20the%20EU%20population, (erişim tarihi: 09.10.2023).

Gogtay, N. J. ve Thatte, U. M. (2017). “Principles of correlation analysis”, Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 65(3), 78-81.

Göv ve Dürrü, Z. (2017). “Göç ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi: Seçilmiş OECD ülkeleri üzerine ekonometrik bir analiz”, Uluslararası Ekonomik Araştırmalar Dergisi, 3(4), 491-502.

Gürbüz, S. (2019). AMOS ile Yapısal Eşitlik Modellemesi. Seçkin Yayıncılık, Ankara.

Hatch, P. (2016). “What motivates immigration to America”, The League of Women Voters, 1-7.

Icduygu, A., Sirkeci, I. ve Muradoglu, G. (2001). “Socio‐economic development and international migration: a Turkish study”, International Migration, 39(4), 39-61.

İlhan, M. ve Çetin, B. (2014). “LISREL ve AMOS programları kullanılarak gerçekleştirilen yapısal eşitlik modeli (yem) analizlerine ilişkin sonuçların karşılaştırılması”, Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 5(2), 26-42.

İslamoğlu, E., Yıldırımalp, S. ve Benli, A. (2014). “Türkiye’de tersine göç ve tersine göçü teşvik eden uygulamalar: İstanbul ili örneği”, Sakarya İktisat Dergisi, 3(1), 68-93.

Kaewnern, H., Wangkumharn, S., Deeyaonarn, W., Yousaf, A. U. ve Kongbuamai, N. (2023). “Investigating the role of research development and renewable energy on human development: An insight from the top ten human development index countries”, Energy, 262, 125540.

Kanbir, Ö. (2022). “Göç ve ekonomik gelişme”, Ekonomi İşletme Siyaset ve Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi, 8(2), 349-365.

Kandemir, O. (2012). “Human development and international migration”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 446-451.

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B. ve McCoach, D. B. (2015). “The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom”, Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486-507.

Keskin, A. (2011), “Ekonomik kalkınmada beşeri sermayenin rolü ve Türkiye”, Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 25(3-4), 125-153.

Khalid, B. ve Urbański, M. (2021). “Approaches to understanding migration: a mult-country analysis of the push and pull migration trend”, Economics & Sociology, 14(4), 242-267.

Lee, E. S. (1966). “A theory of migration”, Demography, 3, 47-57.

Lind, N. (2019). “A development of the human development index”, Social Indicators Research, 146(3), 409-423.

Llull, J. 2017. “The effect of immigration on wages: Exploiting exogenous variation at the national level”, Journal of Human Resources. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.53.3.0315-7032R2

Manga, M., Bal, H., Algan, N. ve Kandır, E. D. (2015). “Beşeri sermaye, fiziksel sermaye ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi: Brics ülkeleri ve Türkiye örneği”, Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 24(1), 45-60.

Marger, M. N. (2001). “Social and human capital in immigrant adaptation: The case of Canadian business immigrants”, The Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(2), 169-170.

Massey, D., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A. ve Taylor, E. J. (2014). “Uluslararası göç kuramlarının bir değerlendirmesi”, Göç Dergisi, 1, 11-46.

Mendola, M. (2012). “Rural out‐migration and economic development at origin: A review of the evidence”, Journal of International Development, 24(1), 102-122.

Mia, M. M., Majri, Y. ve Rahman, I. K. A. (2019). “Covariance based-structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) using AMOS in management research”, Journal of Business and Management, 21(1), 56-61.

Nartgün, Ş. S., Kösterelioğlu, M. A. ve Sipahioğlu, M. (2013). “İnsani gelişim indeksi göstergeleri açısından AB üyesi ve AB üyeliğine aday ülkelerin karşılaştırılması”, Trakya Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 3(1), 80-89.

OECD. (2023). Migrition. https://www.oecd.org/migration/

Oltman, A. ve Renshon, J. (2017). Immigration and foreign policy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Our World in Data. (2023). Human Development Index. https://ourworldindata.org/human-development-index

Popogbe, O. ve Adeosun, O. T. (2022). “Empirical analysis of the push factors of human capital flight in Nigeria”, Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences, 4(1), 3-20.

Ritsilä, J. ve Ovaskainen, M. (2001). “Migration and regional centralization of human capital”, Applied Economics, 33(3), 317-325.

Roy, N. ve Debnath, A. (2011). “Impact of migration on economic development: A study of some selected state”, International Conference on Social Science and Humanity, 5, 198-202.

Sain, K. (2023). “Gelişmekte Olan Ülkelerde Beşeri Sermaye Göçünün Ekonomik Sonuçları: Türkiye Örneği”, ICSSIET Congress, 187.

Savalei, V. (2018). “On the computation of the RMSEA and CFI from the mean-and-variance corrected test statistic with nonnormal data in SEM”, Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(3), 419-429.

Schumacker, R. E. ve Lomax, R. G. (2004). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. Psychology Press, Taylor and Francis Group.

Thakkar, J. J.(2020). Applications of structural equation modelling with AMOS 21, IBM SPSS. Structural Equation Modelling: Application for Research and Practice (with AMOS and R), SSDC, 285, 35-89.

UNDP. (2021). Human Development Data. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks

Urbański, M. (2022). “Comparing push and pull factors affecting migration”, Economies, 10(1), 21.

Wirayuda, A. A. B., Jaju, S., Alsaidi, Y. ve Chan, M. F. (2022). “A structural equation model to explore sociodemographic, macroeconomic, and health factors affecting life expectancy in Oman”, Pan African Medical Journal, 41(1).

Yaylali, M. ve Lebe, F. (2011). “Beşeri sermaye ile iktisadi büyüme arasındaki ilişkinin ampirik analizi”, Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 30(1): 23-51.

Yazan, Y. (2014). İnsan hakları bağlamında Avrupa Birliğinin yasadışı göç politikası: Türkiye örneği (Yüksek Lisans Tezi). İstanbul Üniversitesi.

Yılmaz, V. ve Varol, S. (2015). “Hazır yazılımlar ile yapısal eşitlik modellemesi: AMOS, EQS, LISREL”. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, (44), 28-44.

Yılmaz, Z., & Danışoğlu, F. (2017). “Ekonomik kalkınmada beşeri sermayenin rolü ve türkiye’de beşeri kalkınmanın görünümü olarak insani gelişim endeksi”, Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, (51), 117-147.

Zanbak, M. ve Özgür, R. Ö. (2019). “İnsani gelişme endeksi bağlamında Avrupa Birliği’ne üye ve aday ülkelerin karşılaştırmalı analizi”, Journal of Management and Economics Research, 17(2), 175-192.

Beyan ve Açıklamalar (Disclosure Statements)

1. Bu çalışmanın yazarları, araştırma ve yayın etiği ilkelerine uyduklarını kabul etmektedirler (The authors of this article confirm that their work complies with the principles of research and publication ethics).

2. Yazarlar tarafından herhangi bir çıkar çatışması beyan edilmemiştir (No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors).

3. Bu çalışma, intihal tarama programı kullanılarak intihal taramasından geçirilmiştir (This article was screened for potential plagiarism using a plagiarism screening program).